Archive

Fun with Grove Words and Cipher Wheels

What is a Grove word? The answer is a little fuzzy, but simplistically a Grove word is a VMS word that begins with one of the gallows glyphs. These words are often page or paragraph initial. Emma May Smith has a good explanation in her recent blog entry.

Mr. Grove observed the peculiar feature that some words beginning with a gallows glyph are also valid words if you remove the gallows glyph. For example, the word EVA kodaiin starts with gallows k, and odaiin is also a valid word.

It turns out that if you look at all words in the VMS, 46% of them have this property: remove the first glyph and you are left with a valid VMS word. Compare this with English, where only around 8% of words produce valid words if you remove the first letter. Making up the 46% we have 38% from non-Grove words (i.e. non-gallows initial), and 8% from Grove words.

To round out the statistics, about 13% of all VMS words have an initial gallows glyph.

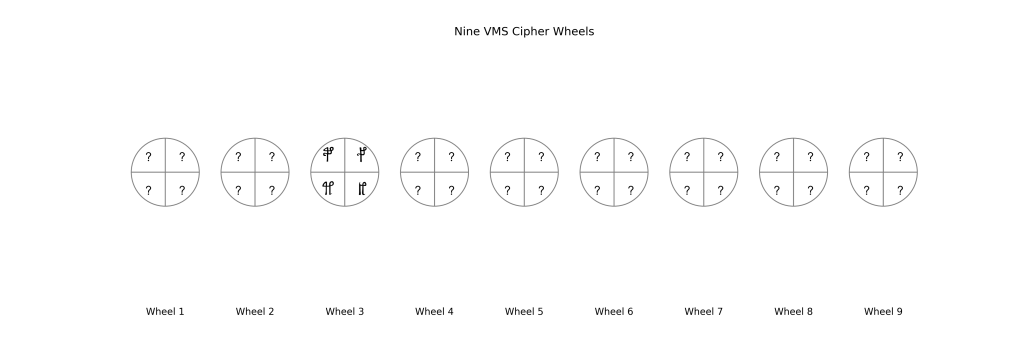

Consider the nine wheels above, where one of the wheels contains gallows glyphs, and the other wheels contain other glyphs. These wheels can be selected in 29 -1 i.e. 511 different ways, to make words of length between 1 and 9.

The probability of selecting wheel 3 as the first wheel for the word is about 12.5%. In other words, with these 9 wheels, 12.5% of the time we’d create a gallows-initial “Grove” word – very close to what we observe in the VMS (13%). In fact, this figure of 12.5% is independent of the number of cipher wheels: as long as there are at least three wheels and they are used left to right, and the gallows glyphs fully occupy the third wheel, then 12.5% of the generated words will be Grove types.

As a corollary, it’s clear that for Grove types generated with the wheels, removing the first glyph will produce a valid word, as it is equivalent to generating a word starting at wheel 4 or later.

So what of the 54% of VMS words that are non-Grove, i.e. removing the initial glyph does not produce a valid VMS word? This can be explained if the number of different words used and written in the VMS is simply less than the total number of possible words that the author’s wheels can produce. What is the expected vocabulary size if we know there are 7,552 words written in the VMS (Takeshi), and we are missing 54% of them? It is simply 1.54 x 7,552 = 11,630 words, or thereabouts.

(Aside: the wheels above could just as easily be represented and used as a table with nine columns.)

In summary, “Grove” words (gallows initial) are ~13% of all words in the Voynich manuscript, and this fraction is what you’d expect if the text was produced using cipher wheels.

Alfonso X’s Lapidario: Stones, Stars and Colours

I’ve been down a bit of rabbit hole over the last couple of days which others may have already been down. I was looking once more at the Zodiac folios, in particular Taurus. The Taurus Light and Dark folios are both marked “may” in, as often remarked, a later hand. There are 15 figures in each Taurus folio, for a total of 30. However, as we well know, May has 31 days, so the figures probably don’t represent days. I thus went in search of 30-way splits of Zodiac signs ….

Alfonso X’s Lapidario

Looking at this old Spanish illustrated manuscript:

“Tratados de Alfonso X sobre astrología y sobre las propiedades de las piedras”

which is a treatise on astrology and the importance of stones/gems etc., we can see a circular Taurus diagram with 30 divisions.

Each of these divisions is associated with a stone, of a noted colour, and one or a few stars in a constellation. There is a lengthy description of each division, its stone, its stars, the various ailments the stone cures, when the stone should be used, et cetera. There is a Spanish transcription of the text here, which I found very useful (combined with Google Translate):

Since a plausible language match to the month spellings as written in the Zodiac folios is Occitan which at one point covered part of Spain (please correct me on this, as I’m not sure), there seems to be a compelling regional match here, but I can’t quite figure it out.

From what I’ve read, Alfonso X assembled a team of scholars from all world regions, who worked on documents on a variety of topics. This website says of the Lapidario: “The Lapidario is a thirteenth century Castilian translation sponsored by King Alfonso X el Sabio, the Learned. The translation was done from an Arabic text which in turn is said to have been translated by the mysterious Abolays from an ancient text in the “Chaldean language””

Matching Stone Colours

Anyway, my first approach was to try to match the colours of the headgear or tunics of the clothed figures in the Taurus Light folio to the colours of the first and second fifteen stones mentioned in the Lapidario. It’s a little tricky, because although the stones are numbered, we don’t know which is figure 1 in the Taurus Light folio, and whether the inner ring precedes the outer. Even so, the patterns of colours in the stones sequence might reveal a match. I drew a blank.

Matching Stones with Voynich Star Labels

My second approach was to try to match the names of the stones with the labels on the figures, to see if there was some correlation between the label length, or its initial glyph, with the stones’ names. Very tricky.

Some of the stones that appear in the Taurus set of 30 also appear in other Zodiac signs in the Lapidario. For example, the ninth stone in Taurus is “esmeri(l)” (Latin), and esmeril is also the third stone of Libra, and the second stone of Aquarius.

This leads to the obvious question: is there a Figure in the both the Voynich Taurus and Libra roundels (Aquarius is missing) that shares the same label? If so, might that label be “esmeril”? And, are there other stones that appear in more than one sign which might be matched to duplicate stones in the Lapidario?

(As an aside, regarding the stones and colours, I was struck by the third stone of Taurus, called “camorica”, which is scarlet in colour and associated with the Pleiades.)

Another promising avenue is to compare the shapes and orientations of the stars in the constellations as they appear in the VM with how they appear in the Lapidario. Since the Pleiades are mentioned in the Lapidario, are they illustrated there, and does its illustration of the cluster match the apparent drawing of it in the VM (which differs in detail from its actual appearance in the night sky)? I need to investigate further, but my suspicion is that others have already been down this path 🙂

Chaldean Stones

I extracted the Chaldean stone names for each Zodiac sign, from the transcription I linked to above. The stones for Aries are shown below, as an example. (The whole set is available if anyone wants it.)

The first 12 sections in the Lapidario list the 30 stones for each zodiac sign, but a few signs appear to be truncated: Leo has only one stone, Pisces only has two stones, and Aquarius only 28.

There follow more sections, again one for each sign, but these each have only three stones. I’m not clear what they represent. I posted about all this at Voynich Ninja, and MarcoP was able to explain. Others also chimed in with some useful comments. The discussion is here.

Anyway, following those sections are several more that cover the stones of Saturn (4 stones), Jupiter (4 stones), Mars (4 stones), Venus (24 stones), Sun (9 stones) and Mercury (17 stones).

Here is an extract of the list I extracted for all the Zodiac stones: this is for Aries.

ARIES 1 magnitad 2 zurudica 3 gagatiz 4 miliztiz 5 centiz 6 movedor 7 goliztiz 8 telliminuz 9 milititaz 10 huye de la leche 11 alj?far 12 anetatiz 13 beruth 14 piedra de cinc 15 tira el oro 16 chupa la sangre 17 parece en la mar cuando sube Marte 18 tira el vidrio 19 annora 20 yzf 21 cuminon 22 astarnuz 23 belyniz 24 gaciuz 25 azufaratiz 26 abietityz 27 lubi 28 ceraquiz 29 berlimaz 30 annoxatir

In total I count 301 stones in the Lapidario’s Zodiac section, of which 291 are unique to a sign. The remainder appear more than once as follows:

bezaar [(9, 'G\x83MINIS'), (11, 'G\x83MINIS')] azarnech [(12, 'SAGITARIO'), (13, 'SAGITARIO')] pez [(7, 'LIBRA'), (30, 'LIBRA')] plomo [(18, 'VIRGO'), (13, 'CANCRO')] calcant [(10, 'VIRGO'), (11, 'VIRGO')] aliaza [(23, 'TAURO'), (29, 'TAURO')] parece en la mar [(15, 'SAGITARIO'), (15, 'TAURO'), (17, 'G\x83MINIS'), (17, 'ACUARIO')] de la serpiente [(12, 'LIBRA'), (7, 'G\x83MINIS')]

e.g. “bezaar” is the 9th and the 11th stone in Gemini, “de la sepiente” is the 12th stone in Libra and the 7th in Gemini.

Turning to the Voynich Zodiac, I count 298 unique star labels of which 269 are unique to a sign. The labels that appear more than once are:

otal dar ['71r', '70v2'] Aries (Light) , Pisces , otal ['72r2', '73r'] Gemini , Scorpio , okeey ary ['72r1', '72r2'] Taurus (Dark) , Gemini , okal ['73v', '72r2', '72r2'] Sagittarius , Gemini , Gemini , okeos ['73v', '73r', '73r'] Sagittarius , Scorpio , Scorpio , okeoly ['70v2', '72v1'] Pisces , Libra , otaly ['70v2', '72v3', '73r'] Pisces , Leo , Scorpio , okaram ['70v2', '72r2'] Pisces , Gemini , okoly ['70v1', '72v3'] Aries (Dark) , Leo , okalar ['72r3', '72r2'] Cancer , Gemini , okary ['72v3', '73r'] Leo , Scorpio , okam ['72r2', '72v3'] Gemini , Leo , okeody ['73v', '73v', '73r', '72v2'] Sagittarius , Sagittarius , Scorpio , Virgo , ykey ['73v', '73v'] Sagittarius , Sagittarius , okaly ['70v2', '72r2', '72r2', '72v3'] Pisces , Gemini , Gemini , Leo , okaldy ['72r2', '72v3'] Gemini , Leo , otaraldy ['72r1', '72r2'] Taurus (Dark) , Gemini , otoly ['72v3', '73r'] Leo , Scorpio , oky ['73v', '72v3', '73r'] Sagittarius , Leo , Scorpio , oteody ['73v', '73v'] Sagittarius , Sagittarius , okedy ['72v1', '73r'] Libra , Scorpio ,

e.g. “otal dar” appears as a label on both the Aries(Light) and Pisces zodiac chart.

If the Voynich Zodiac charts are indeed showing stones (and the figure/star labels are their names), then there should be good matches between the two lists above.

One potential match is:

azarnech [(12, 'SAGITARIO'), (13, 'SAGITARIO')] ykey ['73v', '73v'] Sagittarius , Sagittarius ,

However, the two labels “ykey” on f73v are not adjacent, which they should be if they are stones 12 and 13.

Another:

azarnech [(12, 'SAGITARIO'), (13, 'SAGITARIO')] oteody ['73v', '73v'] Sagittarius , Sagittarius ,

in this case, the two labels “oteody” on f73v are adjacent to one another, but the figures/stars they label are in the group of four at the top of the folio: it’s a stretch to think their locations are 12th and 13th.

To be continued ….

Common Words in Language A that are Rare in Language B

The question was posed: which words are common in Language A but rare in Language B? And vice versa.

For this study I used the Herbal/Balneo folios that are Language A and B respectively (folios 1-25 and 75-84).

There are around 2900 unique words in total, with around 1600 being used in Language A, and 1630 in Language B.

Here are the results. The tables show the words in order of decreasing value of the frequency in A (B) divided by the frequency in B (A), and show the number of occurrences of each word in both Languages.

Conclusion? I have no idea … for now.

Single glyphs in Language A and Language B

Chromosome ['o', '9', '1', 'a', 'H', 'c', 'e', 'h', 'y', 'k', '2', 's', 'm', '4', 'i', '(', '8', 'p', 'g', 'n']

ngramsA ['o', '9', '1', 'a', '8', 'c', 'e', 'h', 'y', 'k', '2', 's', 'm', '4', 'g', 'i', 'K', 'p', '?', 'n']

This shows that most Language B glyphs map to the same glyph in Language A. However, there is some mixing going on here between “H”, “8”, “i”, “g”, “(“, “K” and “?”

Chromosome ['o', '9', '1', 'a', 'i', 'g', 'c', 'y', 'k', 'e', 'h', 'N', '2', 's', '4', '(', '8', 'p', 'f', 'H']

ngramsA ['o', '9', '1', 'a', 'i', '8', 'c', 'e', 'h', 'y', 'k', 'N', '2', 's', '4', 'g', 'K', 'p', '?', 'H']

- e and y swap between languages

- h and k gallows swap between languages

- some mixing of g,8,(,K,f,? – some of these are relatively rare, so the statistics are poor, which may explain the mixing.

seek = ["3", "5", "+", "%", "#", "6", "7", "A", "X", "I", "C", "z", "Z", "j", "u", "d", "U", "P", "Y", "$", "S", "t", "q", "m", "M", "n", "Y", "!"] repl = ["2", "2", "2", "2", "2", "8", "8", "a", "y", "ii", "cc", "iy", "iiy", "g", "f", "ccc", "F", "ip", "y", "s", "cs", "s", "iip", "iiN", "iiiN", "iN", "y", "2"]

The Relationship Between Currier Languages “A” and “B”

Captain Prescott Currier, a cryptographer, looked at the Voynich many moons ago, and made some very perceptive comments about it, which can be seen here on Rene Zandbergen’s site.

In particular, he noticed that the handwriting was different between some folios and others, and he also noticed (based on glyph/character counts) that there were two “languages” being used.

When I first looked at the manuscript, I was principally considering the initial (roughly) fifty folios, constituting the herbal section. The first twenty-five folios in the herbal section are obviously in one hand and one ‘‘language,’’ which I called ‘‘A.’’ (It could have been called anything at all; it was just the first one I came to.) The second twenty-five or so folios are in two hands, very obviously the work of at least two different men. In addition to this fact, the text of this second portion of the herbal section (that is, the next twenty-five of thirty folios) is in two ‘‘languages,’’ and each ‘‘language’’ is in its own hand. This means that, there being two authors of the second part of the herbal section, each one wrote in his own ‘‘language.’’ Now, I’m stretching a point a bit, I’m aware; my use of the word language is convenient, but it does not have the same connotations as it would have in normal use. Still, it is a convenient word, and I see no reason not to continue using it.

We can look at some statistics to see what he was referring to. Let’s compare the most common words in Folios 1 to 25 (in the Herbal section, Language A, written in Hand 1) and in Folios 107 to 116 (in the Recipes section, Language B, written in a different Hand):

So, for example, in Language A the most common word is “8am” and it occurs 192 times in the folios, whereas in Language B the most common word is “am”, occuring 137 times.

We might expect that these are the same word, enciphered differently. The question then is, how does one convert between words in Language A and words in Language B, and vice versa? In the case of the “8am” to “am” it’s just a question of dropping the “8”, as if “8” is a null character in Language A. In the case of the next most popular words, “1oe”(A) and “1c89″(B) it looks like “oe”(A) converts to “c89″(B). And so on.

If we look at the most popular nGrams (substrings) in both Languages, perhaps there is a mapping that translates between the two. Perhaps the cipher machinery that was used to generate the text had different settings, that produced Language A in one configuration, and Language B in another. Perhaps, if we look at the nGram correspondence that results in the best match between the two Languages, a clue will be revealed as to how that machinery worked.

This involves some software (I’m using Python now, which is fun). The software first calculates the word frequencies for Language A and B in a set of folios (the table above is an output from this stage). It then calculates the nGram frequencies for each Language. Here are the top 10:

The software then runs a Genetic Algorithm to find the best mapping between the two sets of nGrams, so that when the mapping is applied to all words in Language B, it produces a set of words in Language A the frequencies of which most closely match the frequencies of words observed in Language A (i.e. the frequencies shown in the first table above).

Here is an initial result. With the following mapping, you can take most common words in Language B, and convert them to Language A.

A couple of remarks. This is an early result and probably not the best match. There are some interesting correspondences :

- “9” and “c” are immutable, and have the same function

- Another interesting feature is that “4o” in Language B maps to “o” in Language A, and vice versa!

- in Language B, “ha” maps to “h” in Language A, as if “a” is a null

In the Comments, Dave suggested looking at word pair frequencies between the Languages. Here is a table of the most common pairs in each Language.

For clarity, I am using what I call the “HerbalRecipesAB” folios for this study i.e.

Using folios for HerbalRecipeAB : [107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

More results coming …

How was the Voynich Manuscript text written?

I’ve spent many happy hours poring over the text, and am convinced that it is not as “simple” as it appears (i.e. the “words” are not words at all). Here are some conjectures:

- The lines look like they are written left to right i.e. the glyphs were written down from left to right, but were not.

- The scribe started with the drawing and started writing glyphs at various positions on the page.

- The method used for choosing each glyph and for deciding its position involved a mechanical apparatus, perhaps a set of co-rotating cipher wheels that were used to convert each character in the Latin plaintext into a VMs glyph and page position

- The apparatus is set to a new starting position for each folio/page (so e.g. Bettony labels on the three folios the plant appears on are different)

- The density of ink is a clue to the order in which the glyphs were written (nib/quill freshly dipped and full of ink, or almost dry)

- At some point the scribe finishes writing the needed glyphs, and then fills out the spaces with pseudo-random words.

- There is no punctuation because what is seen are not words. What is seen makes no grammatical sense because the glyphs are not ordered and positioned linearly across the page.

- Perhaps the secret to unwinding the cipher is in the labels. The labels on one page are constrained to have been produced by the same initial position of the cipher apparatus, and they must come from the plaintext label.

There are so many clues as to what is going on, yet putting them all together is hugely challenging

For example, Jim Reeds suggested years ago that the order in which the text had been written on the sunflower page, f33v:

was first the text to the left of the left stalk, second the text in between the stalks, and finally the text to the right of the last stalk. This is compelling, since the ink density looks different, and the lines don’t line up well across the stalks. It becomes clearer if you saturate the image:

f33v Saturated

And in that image, what jumps out are the glyphs that are darker than the others. Those can be seen more clearly in black/white:

f33v monochrome drop

where the “o”, “y”, “8”, “e” stick out like sore thumbs. Most of those are in the left section, some in the middle, and fewer in the right. Why are these glyphs bolder, why are they inked more heavily? Were these the glyphs initially placed on the page, and contain the real information, and the rest, unimportant and pseudo-random, were all added later to make the text look “normal”?

Copy and Conversion Errors

Here is a piece of Greek from the Vienna Dioscurides.

Take the second line of text: we can make a simple substitution cipher to convert the Greek characters to Voynich glyphs:

Now suppose there is a second step, where the Voynich glyphs are re-arranged into “words” according to some rules, and are then written into the manuscript.

So where am I going with this? Depending on how easily the original Greek characters are read (e.g. some lines are faint), and whether the characters are recognised correctly, would change the choice of which Voynich glyph to use. If a very old manuscript was being enciphered, this would probably be the case. Besides which, the mapping between a Greek character and a Voynich glyph might change depending on e.g. a table of equivalent characters/glyphs, or a choice of substitution cipher.

Thus if a) the original text is in a language unfamiliar to the scribe, and/or b) the original text is indistinct or otherwise hard to read, then the process of converting it to ciphertext causes errors. The same Greek letters might end up being enciphered differently depending on their readability.

f75r cures, pregnancy, life and death – Latin Plainchant

Here is a result obtained using a Genetic Algorithm to match the text on f75r to Latin. The training corpus I used was a large file of Latin plainchant (the idea being that repeated “words” in the VMs show similarities to chant).

First, here is the folio with the translated words overlain in red:

The genetic algorithm searched for a set of glyphs that each matched to a pair of Latin letters.

Most of the decrypted words are valid Latin and match words in the plaintext I used to train the GA. Some are Latin but do not appear in the plaintext. The other, invalid, words could be caused by errors in the pair matching.

Or the whole thing could well be nonsense! This is likely – I asked Joel Stevens to translate some of the Latin, and here is what he said:

On first inspection, it seems to be random non-sense. For example:

recita lugete vena dans veta ia debent lustrata liteWould mean: Recite! Mourn! Blood-vessel giving. Forbid! Oh, they owe things that were purified by the lawsuit.

I’m not really sure how to make sense of it. I don’t see anything that stands out as an obvious sentence. Maybe some words are filler and need to be dropped… or maybe there is a hidden order that needs to be found (assuming these are the correct words).

Here is the Latin:

piraextita recita' lugete' idpirata lucrte vena' dans' veta' ia' debent' lustrata' vanagete vamirata lite' lugens' esnt levata' nuta' gens' veanta rochum' nogete le dato' uascie excita' curi gent na veta' le veta' luedicta veexti vata' arta' te' chum no' no' amicta' luedet luga' mori' edente' noga date' reri' lugens' feta' luedicta luga' morata' luaena uechum vana' lugete' ad' nt vana' luga' pate vata' lugertta audita' lugens' vita' curata' resona' lupina' feta' lumina' lugeum veon lugete' no' vana' lant aule lucrte ista' veta' lugens' vita' na ruri' mena' strata' luedicta lugens' nota' luedicta na lugent' reti' vena' date' vageas dedita' lugent' nota' veta' te' no' iret' veta' na no' vena' luga' morata' edicta' lumina' lumina' lumina' lumina' lugens' novena' lace' si' educta' lugens' na novena' lugens' vita' lugens' ruti' sita' lans' lugens' luuacinota lacium vana' pant' le vena' reista luga' aurata' lugete' verata nt ha' urgens' ad' revena lugens' vana' morati' vemota curatita dant' bunt' id' ncnt vena' lugeas pant' vesata lunt vena' lunt ruchum este' late' nota' luaerata lunt veta' luga' veta' ulta' lugens' ti iu' veta' lute vata' stri sschum veta' lumicium clrechum vata' poma' le sebete no' te' ut' sati' veta' lugens' vana' le acta' gete vana' tute' mori' aeri' luedet lugent' deri lunt vana' lugeas lugens' no' edet' luuatita lans' vato te' no' lans' orta' luedicta id' na luedicta strata' tuas' dans' no' veno dans' no' luia' date' muta' gnsiurte duno' luca' alti' vena' resina' date' ruti' rurata na sunt' errata' morata' luedet pant' no' dace' veto' lunt nt amicta' luedicta strata' dans' fisi' na uachns no' recina lunt dans' novata' luedicta vana' lucrum' lu' dans' irquta lumita lugens' vaga' lugent' dans' vana' resino vena' reti' nodo' aurata' lumita vita' lugete' vena' vata' lumini' lumina' dant' na locuta' dant' vena' lugens' date' pena' vena' lugete' vena' usta' luedet nt vena' lunt vana' lugens' ferata rorata' dalias pr' nomina' resi date' ruta reti' ruti' no' gens' nomina' lugens' ambita' lugens' date' date' vena' lugens' nona' pant' mirata luedicta luncta' reti' ruti' date' date' na lumina' na ambita' lumina' luedicta lumiista nt lumirata luedicta lumina' lumina' lumirata usta' serata' luedicta lumirata noedicta ruri' ncusta date' vena' lugens' vena' dant' edicta' te' vena' paedicta luedicta rucina luga' na edicta' ma aurata' lumina' luedicta luiget luigicta date' serata' vagete nona' lugens' fiti ruti' nona' sprata lans' rerata lumina' rurata renona ruti' ruut nochns ha' date' na derata orta' lumita rerata lalint ruta rurata lumena rurata rechns lumita lumina' veno lumina' dans' vena' eg plnt vana' noti'

An abjad result from the Genetic Algorithm

Here is one of the GA results. This is an attempt at deciphering the text on f9v (the Viola plant). The VMs words on that folio are:

"fo1oy","ogoyo89","og9","2oy","4og19j1o","4ofoe","2oe", "81oy","1oe","1oy","89","ok9","89", "9hc9","1oy","oh9","occcs", "9kc9","k19","okoe","ok9","koe89", "g1oy","9j1cc9","4okoy","9j19","kc","ay","1k9", "o8oe","1o9","h2co89","1o89","ok19","9ha", "4o","1oe","1oe","okae","8oy", "4oh1o","yoh98","8ae9", "19","kay","19k9","8ay9","9koe89", "ok9","h1oe","1oe","19","h9k9", "91oy","12ok9","1oy"

These are not all the words on the folio: I have removed those that contain unusual or problematic glyphs (e.g. the “m”).

The GA comes up with the following VMs->Latin character mapping:

Voynich: o 9 1 k y 8 e c h a 4 g 2 j f s Plain: r s d p m b t n f l q c x v g

And here are the deciphered words. On each line you have the VMs word, the Latin consonants, then the possible Latin or English words in the dictionary that match the abjad.

fo1oy = vrdrm = virdiarium viridarium viridiarium ogoyo89 = rqrmrbs = ? og9 = rqs = requies arquus 2oy = crm = carum coram curam corium cremo cyrum curiam acerum acorum acroama acrum aecoreum careum cereum cerium ceroma coarmi coarmo crami cremii cremi croma cromae curium cream 4og19j1o = rqdsxdr = ? 4ofoe = rvrt = reverti reverto iuraverat 2oe = crt = certa certe certo creta curatio curto creat coarto create cartae caret acerata careota careotae cariota cariotae carota carotae carta carti caryitae caryota caryotae ceratia ceratiae ceratii cerati cerata ceroti certi coertio coryti cratio creatio creati creata cretae cretea cretio crita critae croto curate curata curiatia curiata curito curta ocreata court courte curt cart 81oy = bdrm = obdormio 1oe = drt = audierat deerat oderit odorati aderat auderet durat diruat daret deaurata adaeratio adoratio deartuo deorata deratio diratio dirutio duratio duritia duritiae duritiei odoratio odorata darte dirty 1oy = drm = audieram darem dierum dormio oderam odorem iudeorum deorum darium adoreum adorium dearmo diarium dirimo diremi dirum dormeo drama dromo durum edormio edurum odorum dram 89 = bs = abs bis bos iubeas iubes basio uobis abusi ibis abies absi abusio baes bas basi bes bios bus ibos obesa obsuo obsui base abuse bees boys busy bays ok9 = rps = repsi rapis aeripes euripus reapse reposui rupes rupis ropes 89 = bs = abs bis bos iubeas iubes basio uobis abusi ibis abies absi abusio baes bas basi bes bios bus ibos obesa obsuo obsui base abuse bees boys busy bays 9hc9 = sfns = sifonis 1oy = drm = audieram darem dierum dormio oderam odorem iudeorum deorum darium adoreum adorium dearmo diarium dirimo diremi dirum dormeo drama dromo durum edormio edurum odorum dram oh9 = rfs = rufus refuse occcs = rnnng = running runninge 9kc9 = spns = sapiens spinas sponsi sponsa supinis spensa spinis yspanos sapineus sapinus saponis siponis sopionis spensae spineus spinosa spinus spons sponsae sponsio sponso supinus k19 = pds = pedes pedis apodis pods okoe = rprt = reperiet reparat eriperet reperta reperit reparatio reperti reporto reporte report ok9 = rps = repsi rapis aeripes euripus reapse reposui rupes rupis ropes koe89 = prtbs = partibus portabis parietibus g1oy = qdrm = quadrum quadrima 9j1cc9 = sxdnns = ? 4okoy = rprm = reprimi reprimo 9j19 = sxds = ? kc = pn = opinio opino paene pene poena pono punio puny upon pane pena pone apiana apianae apina apinae paean paeon paeonia penae peni pinea pini poenae poenio open pen paine pain payne pyany pin pine pan peny peony ay = lm = aliam alium lama lamia lima limo olim almi oleum alme alma aulam alum aulaeum elimo ilum lamae lamiae lema limae limi ulmea ulmi elm 1k9 = dps = dapes daps adeps adipis adipeus adips adipsi adposui dapis deposui depso depsui diapasi o8oe = rbrt = arboreti robert 1o9 = drs = aderas derisui dorso durus odores duros dirus edurus odorus edrus durius diris duris derisio dares adoris adoreus adoriosa adrasi adrisi adrisio adrosi adursi derasi derisi derisa derosi derosa diarius dirasi dorsi odoris deirous dooers doores dryes dries drousie dyers h2co89 = fcnrbs = facinoribus 1o89 = drbs = derbiosa ok19 = rpds = rapidus 9ha = sfl = useful safly safely 4o = r = aer ara aro aurae aure aurea auro ero eruo ira irae ire iuro or ore ori oro re rea rei rui ruo aera aerio ora iura aura era r uero uaria area auri iure iuri ere aeer aerae aerea aerei aeria aero arae areae areo arui aria ariae ari aureae aurei eiero eare erae erui eri euro euroa euri iro orae reae uro uri rai are oure yeare your our youre ear rue year yeer air rye ar 1oe = drt = audierat deerat oderit odorati aderat auderet durat diruat daret deaurata adaeratio adoratio deartuo deorata deratio diratio dirutio duratio duritia duritiae duritiei odoratio odorata darte dirty 1oe = drt = audierat deerat oderit odorati aderat auderet durat diruat daret deaurata adaeratio adoratio deartuo deorata deratio diratio dirutio duratio duritia duritiae duritiei odoratio odorata darte dirty okae = rplt = repleuit repleta repleat 8oy = brm = baioarium barim baioariam brume bireme boarium boreum borium bromi bruma brumae eboreum ebrium ebureum obarmo broom 4oh1o = rfdr = ? yoh98 = mrfsb = ? 8ae9 = blts = oblitus balatus balteus ablatis ablutus abolitus ablatus belatus beluatus bliteus boletus bolites oblatus blites 19 = ds = ades audias audis das deos deus dies duos odiosa dis adso iudeis ydus adesa adsuo adsui aedes aedis aedus dasea daseae dasia dasiae des desuo desui diis dius dos duis edius edus idos odiose udus dayes daies odyous dose ads daisie kay = plm = palam palma pluma pulmo puleium epulum pilum palmo apuliam palium apalum palmae palmea palmi palum paulum pileum plumae plumea plum polium polum palm 19k9 = dsps = dasypus deseps disposui despise 8ay9 = blms = bulimos bulimosa bulimus balms 9koe89 = sprtbs = spiritibus ok9 = rps = repsi rapis aeripes euripus reapse reposui rupes rupis ropes h1oe = fdrt = foederata foederati 1oe = drt = audierat deerat oderit odorati aderat auderet durat diruat daret deaurata adaeratio adoratio deartuo deorata deratio diratio dirutio duratio duritia duritiae duritiei odoratio odorata darte dirty 19 = ds = ades audias audis das deos deus dies duos odiosa dis adso iudeis ydus adesa adsuo adsui aedes aedis aedus dasea daseae dasia dasiae des desuo desui diis dius dos duis edius edus idos odiose udus dayes daies odyous dose ads daisie h9k9 = fsps = ? 91oy = sdrm = siderum sidereum sudarium 12ok9 = dcrps = decerpsi decarpsi 1oy = drm = audieram darem dierum dormio oderam odorem iudeorum deorum darium adoreum adorium dearmo diarium dirimo diremi dirum dormeo drama dromo durum edormio edurum odorum dram